Too Entertained to Believe Part 1

Entering the Poppy Field: From Ideas to Dopamine

As the morning light streamed through my window midway through my sabbatical, I sat reading Richard Lovelace’s The Dynamics of Spiritual Life, when I was suddenly gripped by a sense of horror. Lovelace masterfully outlines how historical renewals—from the Hebrew Scriptures to America’s Great Awakening—typically followed a clear pattern: culture descended into apostasy or depravity, people cried out to God, God raised up a leader, and spiritual renewal or revival ensued. He highlights leaders like Jonathan Edwards and his grandson Timothy Dwight, who boldly engaged and dismantled the prevailing Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment ideologies of their times.

The realization that made the hair on the back of my neck stand up was this: the ideological contest we are in the midst of is like no other. It’s not a war of ideas; it’s a battle being waged while one side is comatose, lulled into a dream-state by the algorithm-induced dopamine loop that surreptitiously took control of our lives, dampened our minds, and quietly took its place at the center of our affections.

As I sipped my coffee and considered Lovelace’s point, I thought of the people I love and have prayed for day after day, year after year. I thought of the church I pastor and the many stories that make up the community God has called me to shepherd. It struck me that many, if not most, are woefully ill-equipped to engage in a conversation about the philosophical merits of the Christian perspective compared to, say, post-Enlightenment thinking or secular humanism. For the most part, they do not read; they scroll. Many have never even heard of the Enlightenment, and fewer still could summarize its core philosophical assumptions.

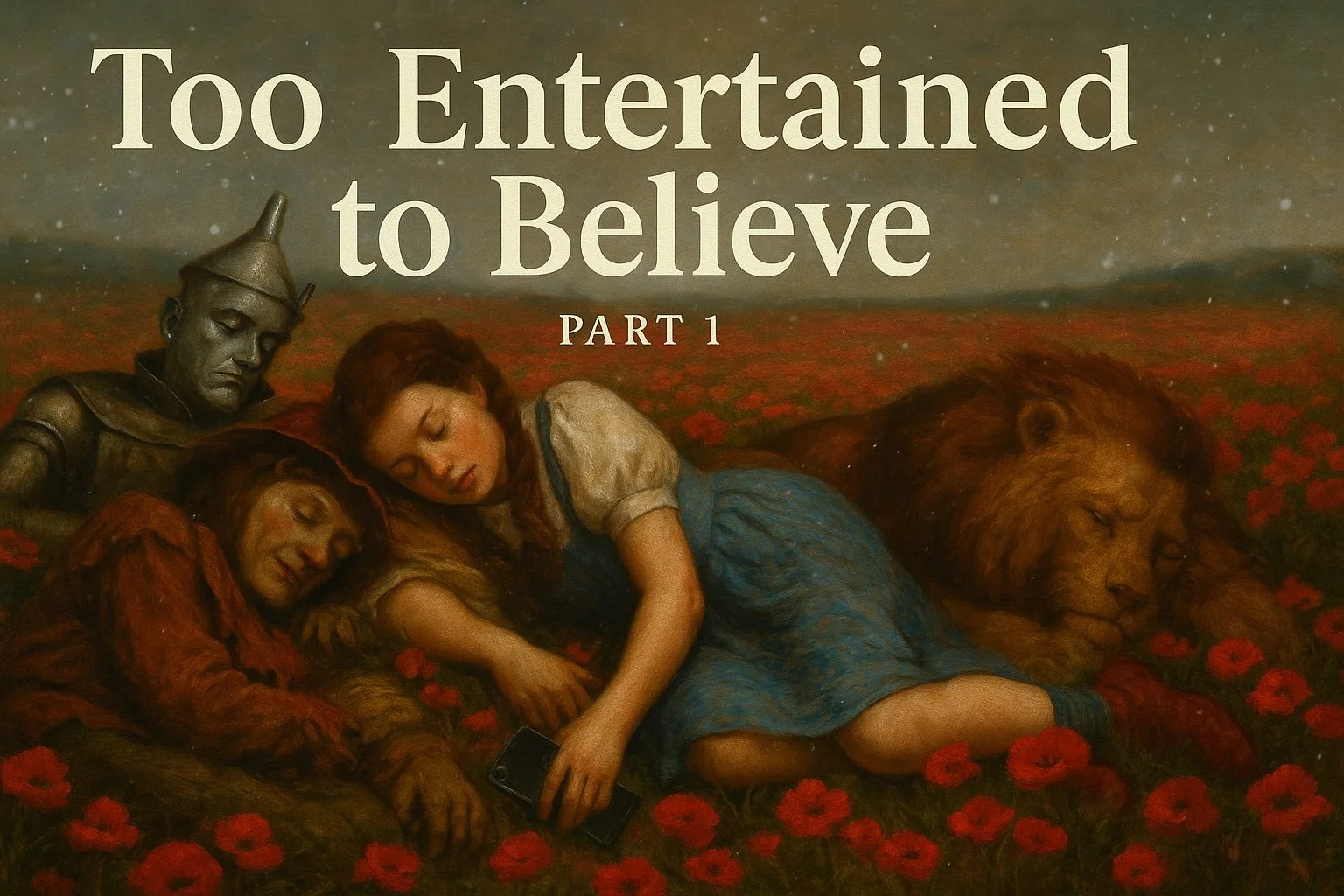

I couldn’t shake the thought that our struggle is no longer a battle of ideas; it is a battle against a neurochemical phenomenon. People are addicted to their screens and, as a result, are inhabiting a kind of cognitive dreamscape, present in body but absent in mind. I was reminded of that moment in The Wizard of Oz when Dorothy and her companions were lulled to sleep in a field of poppies, just short of their destination. The opium-induced slumber was nearly fatal, and the malevolent force behind it nearly triumphed, were it not for the gentle snowfall that roused them and allowed them to continue their journey.

Christians are no longer engaged in the same cultural battles that defined previous generations. A seismic shift has taken place. We are not confronting the logical frameworks of rationalism, the moral ambiguity of relativism, or even the mystical idealism of the Woodstock era. The battlefield has changed. We are no longer in a war of ideas; we are in a war of neurochemistry.

Our forebears may have debated Kant over tea and wrestled with theodicy over whiskey, but we are trying to reach people who rarely engage with serious content and can barely finish a sixty-second video unless it features a cake fail or a dog playing the drums. This is not a struggle of logic; it is a contest for attention, a battle against chemical addiction rather than competing worldviews.

In the 1800s, Timothy Dwight, a legitimate intellectual, was leading Yale University and publicly wrestling with Enlightenment thought. Thinkers of his day attempted to reason their way out of belief in God. Christians like Dwight responded with their best arguments, tight syllogisms, and elegant theology. It was a fair fight: ideas versus ideas.

The 1960s and 70s witnessed the rise of free love, mysticism, and the decline of creedal Christianity. Once again, Christian thought squared off against competing ideologies such as humanism and existentialism, but the contest remained an intellectual one. Today, many Christian thinkers and apologists are still attempting to marshal similar lines of reasoning to confront the dominant forces shaping our culture. But it is the equivalent of bringing a knife to a gunfight.

When Christians attempt to make the case for Christianity in a doom-scrolling, dopamine-saturated culture, Bible in hand, ready to discuss C. S. Lewis and Aquinas, the results are often far less effective than in previous generations. The approach falters because the audience is no longer engaged in a rational search for truth; they are entranced, lying comatose before an endless stream of TikTok dance challenges and funny cat videos. This is not a failure of apologetics; it is a misreading of the terrain.

As Alan Noble, Associate Professor at Oklahoma Baptist University and author of Disruptive Witness: Speaking Truth in a Distracted Age, puts it, the crisis is not that people are skeptical of Christianity; it is that they are indifferent. “People are not asking if Christianity is true anymore,” he writes. “They are asking, ‘Why should I care?’” And they are asking it with one eye on their phone and the other on the delivery status of their Amazon order.

Huston Smith, the respected philosopher of religion, once remarked that the greatest threat to faith is not hedonism, but distraction. The challenge is not Nietzsche or Dawkins, nor the self-assured skeptic on Reddit who believes he has dismantled the Trinity. The real danger is far more subtle and pervasive—distraction, driven by dopamine and flickering screens, quietly eroding our capacity for spiritual attention.

The culture of distraction did not begin with the pandemic, but COVID poured gasoline on the fire. It locked us inside with high-speed internet, endless streaming options, and an ironic surge in sourdough starter kits. Before 2020, I might have scrolled Instagram occasionally. TikTok wasn’t even on my radar. But as the weeks of lockdown turned into months, and I had exhausted everything from Tiger King to MeatEater, I found myself hours deep into a digital haze—watching pizza reviews, UFC knockouts, and Alaskan fishing expeditions without quite knowing how I had arrived there.

I wasn’t searching for truth; I was hiding. Escaping. And I wasn’t alone. A 2021 New York Times study found that adults were spending more than seven hours a day on digital media. That’s not casual scrolling; that’s a part-time job. TikTok’s average user was clocking nearly an hour a day on the app and that’s just what they admitted.

This is not merely a lifestyle issue; it is a spiritual one. Faith requires reflection, wonder, space, and silence. Distraction kills all of that. We are not dealing with a generation that has considered Christianity and rejected it; we are dealing with a generation that has never even thought about it because they are too busy watching dogs on jet skis. We are not spiritually hostile; we are spiritually comatose.